In Texas, reformers within the Democratic Party such as Hogg produced some significant reform legislation in 1891, namely the railroad commission and a law restricting alien ownership of land. But Democrats overplayed their hand by booting advocates of the Alliance's subtreasury plan out of their party in October 1891. Only then did the People's Party in Texas begin organizing in earnest.[21] The events of 1891 left Texas Alliancemen in a quandary. Should they remain loyal to the reform wing of the Democratic Party and help save the appointive railroad commission? Or should they move on to the fledgling People's Party in support of their subtreasury plan and an elective railroad commission?[22] The necessity of defending the Texas Railroad Commission split the Alliance and retarded the third party's emergence in the Lone Star State. Thus, the People's Party had a delayed start in the South, and especially in Texas.

Table 2

Voting in the 1890 and 1892 Gubernatorial Elections

|

|

1890 Governor |

|||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

Democrat |

Republican |

Prohibition |

Non-Voters |

Not Yet Eligible |

|

1892 Governor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Democrat |

47% |

9% |

73% |

17% |

0% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Republican |

14% |

52% |

0% |

25% |

28% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Populist |

38% |

0% |

4% |

0% |

0% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lily White Republican |

0% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prohibition |

0% |

0% |

10% |

0% |

0% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-Voters |

1% |

40% |

11% |

56% |

72% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Mike Kingston, Sam Attlesey and Mary G. Crawford, The Texas Almanac’s Political History of Texas (Austin, 1992), 62-65; Biennial Report of the Secretary of State of the State of Texas, 1892 (Austin 1893, 92-97.

Estimates show the Texas Democratic Party splintered badly in 1892. Ecological regressions suggest Hogg retained slightly less than half of his 1890 supporters, while Clark got 14 percent, and Nugent received nearly 38 percent (see Table 2). Despite the third party's slow start in Texas, the magnitude of Nugent's poll was a serious blow to Hogg's leadership of reform forces the Lone Star State. The GOP fared little better. Almost 40 percent of the 1890 Republican voters rejected fusion with conservative Democrats and declined to vote for governor in 1892. Republicans also fused with, or supported the candidates of, the Populist Party in five of the state's thirteen U.S. Congressional districts.[23] While fusion combined the ballots cast for different parties, vote brokering by GOP leaders frequently did not play well with the party's rank and file.

In the presidential balloting where fusion did not exist, Democrats held on to 62 percent of their 1890 poll, while Populists received 36 percent (see Table 3).[24] Hence the People's Party in its initial statewide campaign drew heavily from former Democrats.[25] Clark captured a majority of those eligible voters who declined to vote in 1890. These probably were traditional Republicans who had not bothered to cast a ballot in a non-competitive, off-year election. The lure of the 1892 presidential race and competitive statewide races brought them back into the political realm

Table 3

Voting in the 1890 Gubernatorial and 1892 Presidential Election

|

|

1890 Governor |

|||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

Democrat |

Republican |

Prohibition |

Non-Voters |

Not Yet Eligible |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1892 PrPresident |

Democrat |

62% |

0% |

62% |

33% |

29% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Republican |

0% |

57% |

0% |

8% |

7% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Populist |

36% |

0% |

17% |

0% |

48% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prohibition |

1% |

0% |

19% |

0% |

1% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lily White Republican |

0% |

1% |

0% |

1% |

5% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-Voters |

2% |

42% |

2% |

58% |

12% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Mike Kingston, Sam Attlesey and Mary G. Crawford, The Texas Almanac’s Political History of Texas (Austin, 1992), 62-65; Biennial Report of the Secretary of State of the State of Texas, 1892 (Austin 1893), 58-87.

In the gubernatorial balloting, Populists picked up 35 percent of those who became eligible to vote with the 1892 election (21 and 22 year olds) compared to the Democratic Party's 27 percent (the estimates in the presidential balloting are 48 percent and 29 percent, respectively). This suggests the youngest voters found Populist reform issues especially relevant to their interests. In particular, Populists spoke to the youngest voter's fears about securing freehold tenure of the land. American tradition held that widespread land ownership was necessary to the survival of individual liberties and the continued vitality of republicanism. Thomas L. Nugent, universally recognized as the leader of Texas Populism, proclaimed the land to be "nature's divinely given opportunity to work."[26] His friend, J.G.H. Buck, agreed that the land issue "had no rival." God had laid upon man "the necessity to labor in order to satisfy his wants" by "graciously furnishing him the material for labor" in the form of the land. Buck surely spoke for many Texas farmers when he proclaimed that "all men have an equal and inalienable right to the use of the land, and that any tradition, custom, or power that denies or prevents this right is morally wrong." [27] James H. "Cyclone" Davis, the third party's most traveled orator, alluded to the growing gap between rich and poor when he argued that Populists sought to establish "an aristocracy of industry, merit, and honor, instead of an aristocracy of wealth, arrogance, and idleness."[28]

Quantitative analysis of the 1892 state and national elections in Texas suggests that Populists owed a lot to their origins in the Southern Farmers' Alliance and Knights of Labor. Counties that claimed an Alliance local in 1890 correlated strongly with the Populist vote. The Knights-Populist correlation was weaker, but significant. Conversely, Clark's following showed a strongly negative correlation to sub-Alliances and Knights locals. Hogg received some Alliance and Knights votes, but not as many as did the People's Party.[29]

What motivated voters to support the Populist ticket? James Turner has argued that those who became Populists "seem commonly to have lived on the fringe of the dominant society."[30] Feelings of social isolation, made such people particularly likely to join rural social associations like the Farmers' Alliance. Historian John Dibbern agreed that the loneliness endemic to rural life was a major factor in the ability of the Farmers' Alliance to recruit members.[31] Samuel Webb, on the other hand, has shown that Alabama Populists were "committed to their land, their farms, their families, and their neighbors."[32] Robert C. McMath Jr. has convincingly detailed a much more active social life among late-nineteenth century agrarians than Turner or Dibbern recognized, which is consistent with Webb's analysis.[33]

Turner's contention about Texas Populists residing on the fringes of mainstream society does have some validity for Texas in 1892. But his assertion must be qualified. Using precinct-level data, the Populist vote shows a negative correlation with both urban areas and railroads. It is important to note, however, that the strongest negative correlation was with the number of rail lines serving a precinct. Turner has argued that Texas Populists lived outside the orbit of urban areas. It would be more accurate to say that Texas Populists lived outside areas where the Texas Railroad Commission was an major issue in 1892.[34] Hogg had a weaker correlation, while Clark voters predictably positively correlated with railroads and urban residence.[35] This suggests that many urban boosters feared railroad regulation might stunt development, and hence opposed the Populists. In attempting to circumvent middlemen with their cooperative efforts, the Farmers' Alliance had threatened the livelihood of town elites.[36]

To further his argument for social isolation, James Turner argued that his Populist counties had fewer religious denominations, and a smaller proportion of their population were church members, than "neighboring" Democratic counties.[37] While this is true of his sample, using statewide data, Democratic counties had only a slightly larger (but not statistically significant) percent of church members. Neither was there a significant difference in the number of denominations. In fact, statewide Populist counties averaged slightly more denominations than Democratic ones did.[38] As Robert C. McMath has noted, "the Alliance was founded by rural people who were part of a dense network of churches, schools, lodges, and extended family groups." His scholarship has revealed a substantially less atomistic social life for the era's farmers than Turner has suggested.[39]

Although Texas had a substantial ethnic population in the 1890s, Populists did not secure a significant proportion of this vote in 1892, except for black voters in a few isolated localities. The third party did best among white southern-born farmers, particularly those who originated from plantation states like Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi.[40] These farmers probably had not been planters, but instead slaveless poor whites from poorer soil regions.[41] Although Czechs, Germans, and African Americans each made up noticeable portions of the Texas electorate in the 1890s, and Populists made some efforts to convert each, the results were negligible. Only in a few localities, like Nacogdoches and San Augustine Counties in East Texas did African Americans make up any significant proportion of the Populist electorate in 1892. The third party's recruiting efforts among Mexican heritage Texans was even more anemic.[42]

Conservative Democrat George Clark, who fused with the GOP for the gubernatorial race, picked up the lion's share of the ethnic vote in 1892, although James S. Hogg showed surprising support among blacks. This could be attributed either to his public stance against lynching or to voter fraud. The dominant Democratic Party was notorious in this era for manipulating both the black and Mexican vote through bribery and/or intimidation. Clark's deeper pockets, however, may have helped him offset some of the usual Democratic Party advantage in 1892.[43] In the 1892 presidential balloting, where fusion did not exist, Republicans did well with Germans, many of whom had been Unionists during the Civil War. Democrats, on the other hand, polled well with Mexicans, who had traditionally supported the dominant party. There were strong positive correlations between Clark's vote and all urban occupation groups in the gubernatorial balloting. But in the presidential balloting, Democrats and Republicans split these votes. This suggests that urban Democrats went over to Clark on the railroad commission issue. This issue had united urban Democrats and Republicans. But prospects for a lasting coalition that would benefit the GOP were slim as the railroad commission receded in importance.

Texas Populists appealed for African American support primarily on the basis of shared economic interests. As one white Texas Populist put it, "They are in a ditch just like we are."[44] This theme resonated across the entire South.[45] Georgia Congressman Thomas E. Watson, for instance, explained to black and white southerners that "you are kept apart that you may be separately fleeced of your earnings."[46] Further, Samuel Webb has argued that "anyone who left the Democratic Party to vote for Populists . . . said in effect, that white unity was less important than other issues."[47] Populist appeals for African American help, however, did not imply social equality. Bruce Palmer claimed that white Populists were just as paternalistic toward the black masses as conservatives.[48] In his biography of Texas black Populist John B. Rayner, Gregg Cantrell made a convincing case for Rayner himself having an ideological predisposition toward this kind of relationship.[49]

Texas Populists, as elsewhere in the South, preferred to appeal directly to black voters, particularly through the Colored Farmers' Alliance. Most Populists considered black Republican politicos to be corrupt.[50] Black Republican leaders, for their part, were hesitant to leave the GOP, for in doing so they would be giving up leadership positions that they were not likely to reacquire in the People's Party. Eventually, however, white Populists in most southern states found it necessary to deal with GOP leaders.[51] This was especially true in North Carolina, where southern Republicans were strongest. In his recent biography of North Carolina Populist Marion Butler, James Hunt argued that the third party leadership actually tried to discourage black recruitment at first for fear of offending potential white recruits.[52] In contrast, Texas Populist leaders openly solicited African American help from the very inception of the People's Party. Although the GOP tottered toward insignificance in Texas in the 1890s, Populist recruitment of African Americans did not bring in enough black votes to allow Populist leaders to completely avoid cooperation with Republicans. Texas Populists and Republicans, for instance, apparently engaged in some form of deal making in five US Congressional races in 1892 and six in 1894. In 1896 fusion occurred for statewide offices, presidential electors, and four US Congressional races.[53] Texas blacks may have been just as interested in the freehold tenure orientation of the People's Party as were whites. But many blacks obviously found loyalty to their old party, physical protection, and social discrimination more important. Where local white Populists, especially sheriffs, protected blacks and openly recognized their communities, such as in Grimes, Nacogdoches, and San Augustine Counties, the third party frequently was successful with black voters.[54] Otherwise, white Populist leaders seemed more disposed to solicit black help than black voters were willing to give it.

The Texas Populist vote of 1892 was overwhelmingly rural. It can be associated with counties that had greater proportions of farmers, particularly farm owners.[55] James Turner's argument that Populist counties tended toward self-sufficient farming, however, needs to be clarified. Third party supporters lived in counties that had undergone rapid agricultural development. Such counties had higher proportions of non-Texas-born white farmers (who were more likely to have been recently settled on the land) and can be associated with the greatest increase in the percent of improved acres during the 1880s and 1890s.[56] Sheldon Hackney and Samuel Webb confirm similar patterns for Alabama.[57] But the correlations between percent improved acres in a county and partisan choice in Texas in 1892 are insignificant.[58] Thus, counties tending toward Populism in the Lone Star State had caught up in development. In fact, counties with the greatest proportion of improved acres planted in cotton tended toward the People's Party. Thus, Populist counties were more fully involved in commercial agriculture than Turner suggests.

Research on agriculture in other states suggests that Texas was not a anomaly. In Kansas, Populists were strongest in the central part of the state where farmers had more recently settled on the land. Peter Argersinger has shown that Kansas Populist farmers were more likely than others to be mortgaged. Likewise, they had lower per capita assessed valuations. In Marshall County, South Dakota, John Dibbern found Alliancemen (who presumably later became Populists) were newly propertied men concerned with providing for their families, who were overburdened with debt.[59]

As in Kansas, Texas Populists showed a small but significant correlation with the percent of acres planted in corn.[60] The crop, however, was less of a commercial enterprise in Texas than Kansas. Texas farmers primarily used corn for animal feed and home consumption in the 1890s. This suggests they were farm owners or mortgagers and lived where relatively more pasture was available B in other words, on poorer farm land.[61] Tenant farmers in the South usually were required to grow cotton only. The correlation between the Soil Capability Index employed by county agricultural agents in the twentieth century and the 1892 Populist vote was weak, but significant and positive for poorer land.[62] Yet as Turner noted, simple poverty does not explain the appeal of Populism. Texas Populists did best where farms were smaller, and thus were more accurately categorized as family farmers. But on a per acre basis, Populist farmers appear to have been just as productive as Democrats.[63] Cotton was a very democratic crop. In Kansas, Peter Argersinger likewise found a negative correlation between the value of farm products per farm and Populism.[64] The third party in Texas was strongest in 1892 where rapid economic change, particularly change caused through the appearance of the railroad within the previous decade, caused a transition between self-sufficiency and entry into the marketplace, with the accompanying threat of tenancy for those unable to keep up. Sheldon Hackney noted a similar trend in Alabama where "rapid economic change threatened the way of life of small independent farmers."[65] As Samuel Webb also noted for Alabama, Populists "resented subversion of settled forms of life by . . . capitalist interlopers."[66]

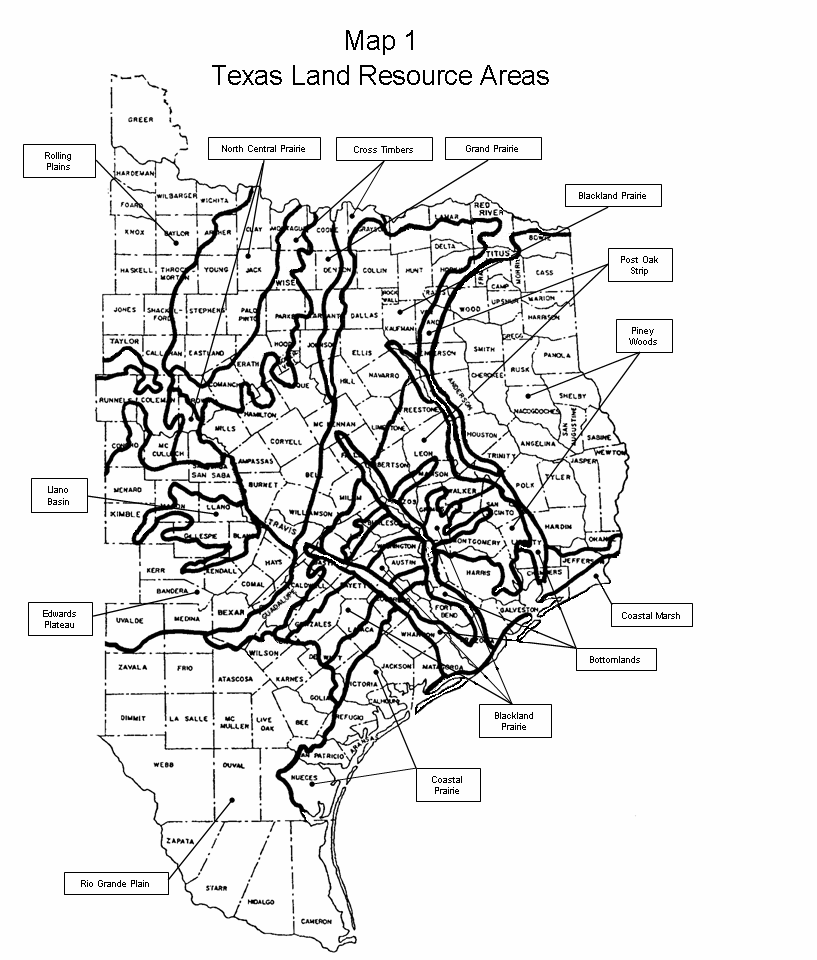

Turner's analysis of Texas Populist voters reveals some significant insights for the 1892 campaign. But it fails to address the diversity within Texas. Roscoe C. Martin long ago noted that third party strength was not uniform throughout the state. He argued that counties favoring Populism had smaller farm holdings and were situated on land that was less desirable for farming. The United States Department of Agriculture has designated fifteen separate Land Resource Areas based upon soil, geology, physiography, vegetation, climate, and land use in Texas (see Map 1). Martin emphasized the differences in these regions in his analysis of who voted Populist. [67]

The Blackland Prairie, which stretched in a narrow strip from the Oklahoma border north of Dallas down to San Antonio, contained the state's most desirable farm land. A smaller, separate strip of Blackland Prairie stretched from about forty miles east of San Antonio to just north of Houston. The main section of Blackland was settled mostly by southern whites, while the smaller section also contained significant mixes of Germans, Czechs, and African Americans. The soil was highly productive and able to withstand heavy and continuous cropping in both areas. Because almost all of this rich land was tillable, farmers tended toward a high degree of specialization in cotton. They maintained smaller livestock herds and grew fewer feed crops. Both Martin and Turner argued that Populism found a cool reception in the Blackland Prairie.[68] But the third party vote in this region in 1892 was only slightly below the statewide average (see Table 4). Here, in this region of highly fertile soil, Populists appear to be those losing out in the struggle for economic independence. The third party correlation with tenancy was stronger than with farm ownership. But, there were no significant correlations between the Populist vote in 1892 and the presence of railroads, which were more numerous here than anywhere else in Texas.[69]

Table 4

Party Vote for Governor 1892-1896 by Land Resource Area

|

|

Statewide |

Blackland |

Post Oak |

Bottom-lands |

Piney |

Cross |

Grand |

All Other |

|

|

Prairie |

Strip |

Woods |

Timbers |

Prairie |

Areas |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1892 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Democrat |

44% |

44% |

41% |

41% |

47% |

48% |

45% |

41% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Republican |

31% |

32% |

32% |

37% |

24% |

19% |

25% |

39% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Populist |

25% |

24% |

27% |

23% |

29% |

33% |

30% |

20% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1894 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Democrat |

50% |

49% |

43% |

43% |

50% |

51% |

50% |

51% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Republican |

13% |

13% |

19% |

21% |

13% |

3% |

5% |

17% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Populist |

37% |

38% |

38% |

37% |

38% |

46% |

45% |

32% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1896 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Democrat |

56% |

55% |

51% |

53% |

56% |

57% |

55% |

57% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Populist |

44% |

45% |

49% |

48% |

44% |

43% |

45% |

44% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Biennial Report of the Secretary of State of the State of Texas, 1892 (Austin 1893), 58-87; Biennial Report of the Secretary of State of the State of Texas, 1894 (Austin 1895), 249-52; Biennial Report of the Secretary of State of the State of Texas, 1896 (Austin 1897), 65-68; General Soil Map of Texas, 1973 comp. by Curtis L. Godfrey, Gordon S. McKee, and Harvey Oakes Texas Agricultural Experiment Station, Texas A & M University in cooperation with Soil Conservation Service, United States Department of Agriculture.

Note: The above percentages represent the percentage of the major party vote that each party received. Lily-White Republican, Prohibition, and National Democratic Party ballots were excluded.

The

Post Oak Strip paralleled the Blackland Prairie to the east. Here the soils

were sandy and covered with timber. Most of the farming was done on

relatively small, interior prairies that had fairly productive soils. Farmers

grew both corn and cotton in this region. Essentially the same tools were

used with both crops, and corn cultivation did not compete substantially with

cotton for labor. Farms were smaller and farm owners more numerous in the

Post Oak Strip. Here, precincts with higher proportions of farm owners tended

toward Populism.[70]

The third party correlation with tenancy was insignificant. Urban areas were

noticeably smaller in the Post Oak Strip. Thus, precinct-level balloting

showed little of the rural-urban or railroad-hinterland dichotomy described by

Turner.

Rich alluvial Bottomlands of the Brazos, Colorado, and Trinity Rivers cross the Post Oak Strip in a northwest to southeast direction. This was the pre-Civil War plantation region, and it still contained a large African American agrarian population in the 1890s. The Bottomlands contained twelve of the state's sixteen black-majority counties.[71] Here the Populist appeal on the land issue resonated best with southern-born whites, who made up the majority of farm owners in this region. The large black population conversely proved ambivalent toward the third party in 1892.[72]

Between the Post Oak Strip and Louisiana border lay the Piney Woods. Sandy soil, rolling to hilly topography, comparatively heavy rainfall, and the persistence of timber gave the fullest encouragement to small-scale operations. Small farms, small irregular-shaped fields, small tools, and the use of large amounts of fertilizer characterized this region. Lack of good pasture discouraged extensive livestock production and, thus, feed crops. Here, a significant negative correlation appears between voting Populist and the number of railroad lines serving a precinct. It was weaker, however, than the statewide correlation. Populations of both African American and whites born in the plantation South were more numerous in this region. The Populist correlation with farm ownership was weaker in the Piney Woods than in the aforementioned regions.[73] Populists in the Piney Woods were less well established and thus more vulnerable to the economic dislocations of the day.

The People's Party did best in the Cross Timbers and Grand Prairie areas to the west of Dallas and Waco. The Cross Timbers is similar to the Post Oak Strip in that hardwoods are interspersed with prairies. The region, however, is dryer. This is where the Southern Farmers' Alliance originated. Again agriculture was undertaken on the prairies and creek bottoms where farmers clustered in distinct communities that encouraged community-spirited mutuality.[74] Cotton was the only important source of income before 1915. Between the eastern and western Cross Timbers lay the Grand Prairie, an almost treeless, rolling prairie with dark, heavy, but stony soils. Cotton and small grains competed for farmland here. Although the area was much better for farming than the Cross Timbers, Populism flourished in both areas. The balance between settlers from the upper South and plantation states was closer in these regions than elsewhere in Texas. But birthplace played little role in political preference. Farm ownership can be associated with the third party vote in these regions, and precincts that went Populist showed a strong and consistently negative correlation to the number of railroad lines serving the precinct.[75] Railroads, which brought the dislocations associated with rapid economic development, first appeared in the area west of Dallas and Waco in the decade before the Populist Revolt. The closing of the open range at the same time, likewise, raised the issue of landlordism and land monopoly.[76] Forty percent of Turner's Populist counties lay in this region. Thus, his analysis relied heavily upon this region's economic and political dynamics.

While the presence of railroads appeared to be a crucial factor in identifying who voted Populist in the Cross Timbers and Grand Prairie, this does not seem to be the case elsewhere in Texas. The correlations in the Blackland Prairie, Bottomlands, and Post Oak Strip are insignificant, while Populists only weakly correlated with the presence of railroads in the Piney Woods. The Populist appeal in 1892 appears to be strongest among farmers whose situation left them most vulnerable to market forces. In less fertile agricultural areas, such as the Piney Woods, Post Oak Strip, Cross Timbers, and Grand Prairie, Populist voters appear to be white farm owners. Their profits margins were smaller, leaving them more susceptible to market fluctuations. In the more commercially dynamic Blackland Prairie, Populists appeared to be white tenant farmers who had already lost out in the struggle for land ownership. Although the Bottomlands were comparatively more developed, tenant farmers in this region tended to be African Americans whose commitment to the GOP remained strong. Here, white farm owners supported the People's Party in 1892.

James Turner interpreted the 1892 Texas Populist's rurality as a sign of isolation from the mainstream of American life in a time when most of the nation was quickly being integrated into the national culture. "The central culture was swallowing more and more of the diverse local cultures," he explained. Isolated, "backward," people like the Populists remained the last outpost of the old America.[77] Certainly the dominant currents of late nineteenth century American thought, namely social Darwinism, laissez faire capitalism, and business boosterism, designated the republicanism of Populism old fashioned and even retrogressive. These newer concepts underpinned the thinking of the Gilded Age's economic and political elite.

Ownership of the land, which made an uncorrupted, independent citizenry the backbone of the nation, was central to the concept of American republicanism. Several scholars, including Robert McMath and Bruce Palmer, have emphasized the importance of the third party's land plank to Texas Populism.[78] Throughout Populism's heyday, both state and national third party platforms demanded government reclaim lands held by railroads and other corporations in excess of what they needed to conduct their business, that non-resident aliens be prohibited from owning land, and that where the conditions of a grant went unfulfilled, the land would be forfeited and opened to homesteading.[79] It was property holding that established a citizen's economic independence. The widening gap between rich and poor that manifested itself in growing tenancy, they believed, would destroy the republic by driving freeholders into a dependent subservience reminiscent of European peasantry. In Texas in 1892, Populists drew most strongly from small farm owners whose status may have seemed timorous, and to a lesser degree from those who had recently fallen into tenancy. Populist strength among new voters in 1892 probably reflected the concern of youthful Texans about ever owning a farm of their own. It was proto-Populists in the 1880s who coined the phrases "Robber Baron" and "Cattle Baron."[80] Their allusions to aristocracy were not just literary license. They believed the economic trends they witnessed were creating a new aristocracy.

Late-nineteenth-century railroads were the purveyors of more than just commercial goods. They also brought the newer, more exploitative culture that threatened the very promise of the older America. As Dorothy Ross has noted, there was a dualistic intellectual nature to American culture during the late nineteenth century. Progressive historians of the early twentieth century clearly understood this and took the side of the Populists. Critics of the Progressive historians frequently have adopted the derisive attitude of Populism's contemporary foes, perhaps without recognizing the underlying premises of such criticism.[81]

Thomas L. Nugent, the Populist candidate for governor of Texas in 1892, recognized that the railroad commission would be the primary issue of the campaign and, thus, considered the Populist's first statewide effort to be educational.[82] The conservative Dallas Morning News, however, warned that the Populists' "earnestness, bordering upon religious fanaticism, has a touch of the kind of metal (sic) that made Cromwell's round heads (sic) so terrible a force in the revolution that ended with bringing the head of Charles I to the block. It would be supreme folly to despise and belittle a movement that is leavened with such moral stuff as this."[83] With the railroad commission issue settled, Alliancemen who had remained loyal to the Democratic Party in 1892 might abandon the dominant party afterward. Populist recruitment, thus, proceeded unabated. One gauge of Populist growth was the significant expansion of newspapers devoted to furthering the third-party effort. Editors almost always played a significant role in the local leadership of the third party. Populists could claim the loyalty of only seventeen newspapers in Texas in 1892. It would grow to seventy five by 1895.[84]

A major factor in the rapid growth of the People's Party after 1892 was general discontent with the national economy. The Panic of 1893 clearly was the worst of America's early industrial period. At its low-water mark, economic activity declined about 25 percent. By the end of 1893, fifteen thousand businesses had closed, and the prices for most farm products (including cotton) had dropped below the cost of production.[85] Northeastern fiscal conservatives attributed the panic to uncertainty about the currency resulting from the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890, which mandated that the federal government purchase certain quantities of silver with notes that could then be tuned in for either silver or gold. Between 1890 and 1893, the redemption of treasury certificates caused federal gold reserves to decline by nearly $132 million. As reserves neared $100 million, entrepreneurs questioned the soundness of the currency and became timid in their investments. In 1893 President Grover Cleveland called a special session of Congress, and after an acrimonious debate, secured repeal of the law. [86]

Men of all parties in the South and West denounced Cleveland's repeal of the Sherman Act. Since the Civil War, the nation's volume of business had tripled, while money in circulation had increased less than 50 percent. The resulting deflation had devastating effects upon the prices that farmers received for their products. Reducing the volume of money further would only aggravate an already desperate situation. Repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act provided Populists with a dramatic issue to promote. Because easterners dominated both mainstream parties, only the People's Party had endorsed free silver in its national and state platforms in 1892. Thus, Populists labeled the repeal a Wall Street plot to make bankers rich and set out to reap the rewards that their pro-silver stance should receive in a state like Texas.[87]

The onset of depression and the popularity of the silver issue in Texas raised serious concerns among Democratic Party leaders about the rapid growth of the People's Party. In January 1894 Governor Hogg offered an olive branch to Clark supporters. The resulting Democratic Harmony Meeting of March 1894 resolved all outstanding differences between the Hogg and Clark Democrats. The move proved prophetic for the Democratic leadership as the Populist vote increased by 40 percent in 1894. The increase was not uniform, but it was statewide.[88]

The People's Party became the major opposition party in Texas in 1894, polling almost three times as many votes as the GOP. Despite Clark's return, Charles Culberson, the Democratic gubernatorial candidate, gained only 16,681 over Hogg's 1892 ballot.[89] He picked up 69 percent of Hogg's and 40 percent of Clark's 1892 vote (see Table 5). Thomas L. Nugent again headed the Populist ticket. He retained 87 percent of his 1892 voters, gained 13 percent of Hogg's 1892 ballots, and 20 percent of new voters. Populists also picked up 10 percent of those who voted for Clark and the 1892 Republican national ticket, probably African Americans. The GOP in Texas was near collapse. W. K. Makemson, the 1894 Republican candidate, retained only 45 percent of Clarks 1892 votes.[90] More ominously for the recently reunited Democrats, Culberson won the 1894 election with only a plurality of the votes cast. Continued Populist recruitment, or fusion with Republicans, could very easily give the third party the crucial election of 1896.[91]

Table 5

Voting in the 1892 and 1894 Gubernatorial Elections

|

|

1892 Governor |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Democrat |

Republican |

Populist |

Lily White Republican |

Prohibition |

Non-Voters |

Not Yet Eligible |

||||||

|

1894 Governor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Democrat |

69% |

40% |

13% |

0% |

0% |

10% |

13% |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Republican |

0% |

45% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

7% |

16% |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Populist |

13% |

10% |

87% |

0% |

11% |

7% |

20% |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Lily White Republican |

0% |

5% |

0% |

17% |

20% |

0% |

0% |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Prohibition |

0% |

0% |

0% |

13% |

7% |

0% |

0% |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Non-Voters |

17% |

0% |

0% |

70% |

62% |

76% |

51% |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

Source: Biennial Report of the Secretary of State of the State of Texas, 1892 (Austin 1893, 92-97; Biennial Report of the Secretary of State of the State of Texas, 1894 (Austin 1895), 249-52

The People's Party in Texas broadened its base of support substantially with the statewide elections of 1894. New recruits included former Alliancemen who had remained loyal to the dominant party on the railroad commission issue in 1892, former Democratic Party silverites, and urban laborers. This was a sharp contrast to Alabama, where Sheldon Hackney found little change in the pattern of voting for the third party between 1892 and 1894.[92] In Texas, Populist gained significantly more support in railhead towns and their environs. This is where unionized laborers resided.[93] The third party also gained strength among voters in areas where urban residence had not been important in 1892, particularly the Bottomlands, Blackland Prairie, and Post Oak Strip.[94] These probably were Alliancemen who had remained loyal to Hogg on the railroad commission issue in 1892. But with that issue settled, they chose to abandon the dominant party for Populism in 1894. Populist Harry Tracy contended in 1915 that Hogg and the railroad commission issue held as many as 50,000 Alliancemen loyal to the Democratic Party in 1892.[95]

There is evidence of an even greater migration of non-Alliancemen to the third party in 1894. The state Democratic platform of 1894 endorsed President Cleveland's pro-gold standard policies.[96] This would drive more prosperous farmers hurt by the depression of the mid-1890 into the Populist fold. It appears that more highly commercialized farmers on better land were migrating to the third party. Populists retained the support of farm owners and sharecroppers, and increased their appeal among the more prosperous cash tenants. But, the third party's correlation with poorer soils decreased into insignificance as more prosperous farmers joined.[97]

George Clark's base of support in 1892 had been urban and ethnic. His return to the Democratic Party in 1894 helped the dominant party with these elements. The GOP became more rural and less ethnic (except for African Americans), particularly losing Mexican-born Texans to the Democratic Party. Culberson also lost many of the African American voters that Hogg had attracted in 1892. Populists gained a bit among non-Texas-born southerners, their strongest voting base. But most African Americans remained loyal to the GOP.[98]

The People's Party also gained among all urban occupation groups in 1894. This was particularly true of railroad workers.[99] The Pullman Strike of mid-1894 involved some Texas workers. Counties with a Knights of labor local likewise correlated better with the Populist vote in 1894 than before. Even more damaging was the state platform's endorsement of President Cleveland's use of federal troops to break the strike. Populist spokesmen nationwide provided substantial verbal support for labor's efforts in 1894. As Matthew Hild has recently noted that long before 1894 there was an incipient alliance between farmers and industrial workers that insured no serious obstacles to farmer-laborer unity would develop in Texas.[100]